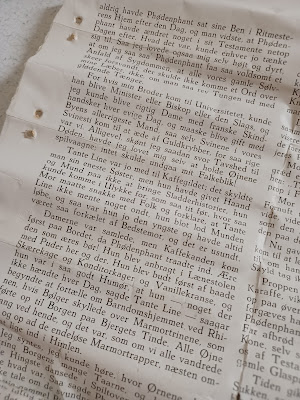

I'm currently remodeling a kitchen in a 120-year-old church. The job is extensive as I tear down the room to the studs and basically start over. As I removed the south wall I saw a paper nailed to a beam. I used my flat head screwdriver to carefully pry up the nail. It was faceted to the wall in such a way as to preserve the writing. It was clearly written in another language and appeared very old.

This area was settled by the Scandinavians and the church was originally The Emanuel Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church.

I reached out to my Facebook friends and found so many people willing to help me translate. I have been told the document is a mix of Old Dutch, Swedish, and Norwegian. It would make sense if this was a page from the Bible, being in a church, but its not and the tale leaves more questions.

Who are these people in the story?

Did this really happen or is it a work of fiction?

Why was it hidden in a church wall?

Translation

by

25 Feb 2022

If my brother came to the

university, he could become a minister or bishop or something like that, and I

could be a proper lady wearing French leather gloves every day and perhaps

marry the town’s richest man, and even the swine in our piggery would eat from

golden troughs, because we were that rich. Nevertheless, even though I’d sworn

to keep quiet until death, I’d promised myself to keep my eyes wide open.

Nothing could avoid my falcon glance.

Aunt Line also came to the

coffee party, one owed one’s sister that much, but she had given hand and mouth

not to share any gossip stories. She could accidently do that, like so often

before, and Mother had to sit and explain to people, that Aunt Line didn’t mean

any harm, she just let her mouth run away, but then again, she was the youngest

and had always been doted on by Grandmother, and that’s unhealthy.

The ladies were gathered, but

the coffee pot wasn’t placed on the table before Phoedenpant entered. Honor to

the one who should be honored! She was carried in the easy chair with powder

here and there. She was offered first, both cake and konditor cake and vanilla

pretzels, and she was in such a good mood, that she—something that didn’t

happen every day, said Aunt Line—even started to talk about the childhood home

by the Rhine, where waves washed up on the marble steps going up to the

fortress on top of the hill. All eyes were on her, and it was as if we all

climbed up and up the eternal marble steps almost into heaven.

I thought I could hear the

eagles screaming around the towers of the fortress and how the white stallions

dancing in the stalls, something I didn’t know what was. Phoedenphant said,

“But let us not speak of days gone by. Now I am a small, poor girl walking on

the edge of the grave.

(Torn page)

And all I can do

to show my gratitude for the town’s hospitality, is to remember each and every

of one’s friends in the last will…”

I sat with my falcon eye to

those pages. When my eyes crossed—my childhood’s greatest “Seg”—I could almost

see around the corners, and I could dare give my two honor fingers as pawn that

not as much as a half a teaspoon would be missing.

The party went wonderful, and

Phoedenphant seemed so happy about Aunt Line’s—what Father called flight of

fancy—that she almost promised to remember Aunt Line “when she least expected

it.”

The guests were hardly out the

door before Mother stood by the table, and I could see her mouth mime, while

she undoubtably counted the spoons and dessert forks. Then she filled her hands

with the silver and let out an enormous sigh.

Mother cleaned off the table

herself, not to risk any of our maids breaking anything. Suddenly, I heard

Mother say, “Child, where is the cork for the carafe?”

“It’s on the table next to the

carafe,” I answered immediately. As that was where I had clearly seen it with

my own eyes. It wasn’t there. Mother said, “It has to be here.” But it was not there.

Just then, Aunt Line returned. She had forgotten her dress belt. Aunt Line

always lifted her dress up to her knees, even if the cobble stones were so dry

you could eat off them.

When she heard about the cork,

she clapped her hands and said, “You can place an ad for that in the paper.

There’s hardly a glass cork left in town, they disappear like last year’s snow,

your Phoedenphant makes sure of that.”

Mother sat down on a chair and

cried bitterly. She was still crying when Father came home, but Father said, Be

sensible about this! What is a glass cork in comparison to the children’s

future?”

Mother was inconsolable. “You

speak according to your sense. There isn’t its likeness in the whole wide

world. It’s unique, I inherited it, as the oldest, and I will be held

accountable for it on the last day.”

Now Father started laughing.

Mother also started laughing, and Father promised to get one exactly the same,

even if he had to steal it. “For Heaven’s sake, don’t put that word in your

mouth,” Mother groaned.

The cork never returned, and

Grandmother’s unique carafe was wrapped in many layers of silk paper and placed

on the top shelf in the pantry, after Mother had suggested to Father that he

should visit Phoedenphant and just accidentally let a word fall. Father

interrupted her, “Are you quite out of your mind, Wife, she would remove us

from her will, and see if you even then would get the old glass cork back.”

Time passed. If it wasn’t for

Mother’s groans and sighs every time she glanced up on the top shelf, I would

have forgotten about the cork a long while ago.

One beautiful day, the whole

town displayed their flags at half pole: Phoedenphant was dead, struck by a

heart attack. The ad was large with a broad black border, written by the

sheriff himself, who deeply regretted that the house’s beloved, oldest friend

had fallen asleep in the Lord. Her memory will not be forgotten.

On the burial day, I was sent

across the bridge with Mother’s flowers for her. The loveliest, little…faith,

hope, and charity tied around the violets.

Mother asked me to place it on

“the chest of the beyond dormant” I had to repeat “the chest of the beyond

dormant” twenty times until I remembered it.

The will was to be opened

straight after the funeral, and there was a greater excitement in town that on

the day of the constitution. Because even if one knew quite a bit, no one knew

everything.

I had black ribbons on my

braids. Actually, I would have blackened my white straw hat with shoe polish to

show I was in proper mourning, as we were among the ones who would inherit, but

Mother wouldn’t hear of it. So, I wandered across Soeder Bridge with the sweet

feeling that the next time I honored the planks on the bridge, I would be one

of the foremost in town with money at the bottom of my coffer. But for now, I

was still a quite ordinary girl with crooked heels.

Oh this seems like a fascinating find!! I wonder if someone hid the book because maybe they weren't allowed to read it?

ReplyDelete